You've completed a unit in science class. How can you capitalize on the student curiosity generated by the experience? Here you'll find guidance on harnessing lingering questions, and get advice for determining next steps.

About This Guide

Below, you’ll find guidance in harnessing your students’ curiosity at the end of a lesson or unit, including:

- How to solicit lingering questions

- How to help students imagine their next steps

- What to do with students’ questions

Because we know teachers appreciate seeing the results of using these strategies, we've also created an example gallery containing student work.

Soliciting Lingering Questions

At the end of a lesson or unit, remind students that scientific investigations don’t just end with results – they end with more questions. Draw out students’ curiosity on the topic by asking them to reflect in their notebooks:

- What are you curious about now?

- What do you wonder?

- What else would you need to find out in order to__________?

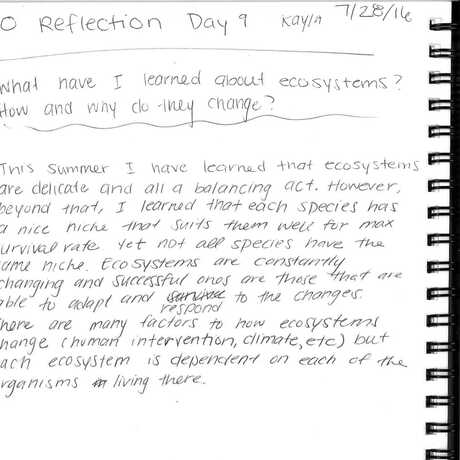

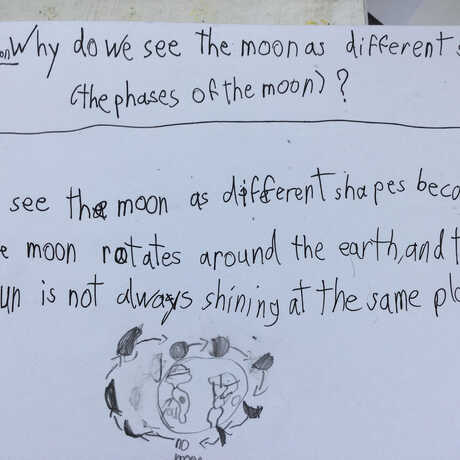

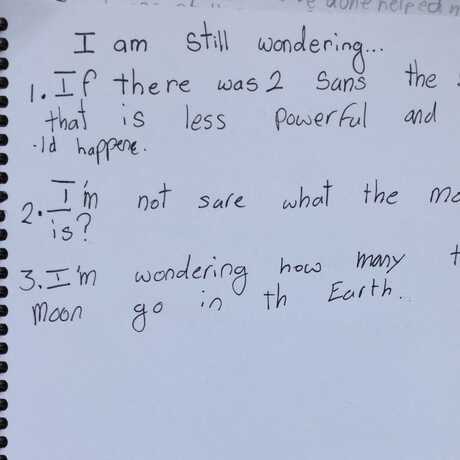

Here's an example of one student's lingering questions about the moon.

Brainstorming Next Steps

Give students an opportunity to imagine how or what they’d like to investigate next. This line of thinking reinforces the fact that science is never finished – it’s an ongoing and iterative process. Ask students to reflect in their notebooks:

- What would you like to try next?

- What materials would you need?

- What else do you think you could figure out about _______?

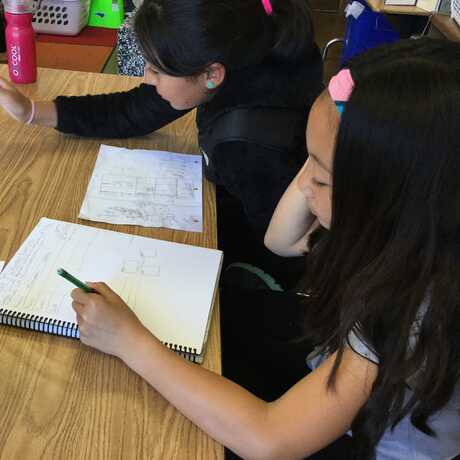

Here's an example of one student planning their next steps for their plant investigation.

What to Do Next

You have several choices for what to do with students’ lingering questions and next steps. Here are a few ideas:

- Just let the questions hang. Put them up somewhere in the classroom so students can continue thinking about them. Asking questions is always worthwhile, even when they are left unanswered.

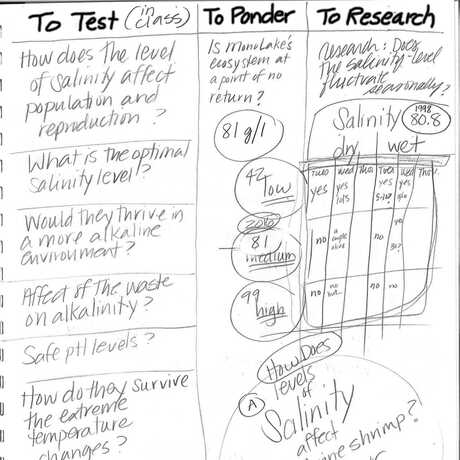

- Work with the students to separate the questions into categories, such as “testable” and “non-testable” questions. Give students a chance to design an investigation to answer one of the testable questions. Here's an example of one group sorting their questions about brine shrimp.

- Create a “question of the week” research corner and let students try to answer some of the researchable questions they generated.

- Give students a chance to illustrate their questions and create a class-wide picture book with one question per page.

- Use the questions as a formative assessment of students’ understandings. Their questions may give you a good idea about what to teach next.

- Go on a relevant field trip and/or invite an expert to field some of the questions.

- Save student questions across the school year and return to them when it’s time for the science fair. These questions can be a great starting place for individual projects.

Notes from the Classroom

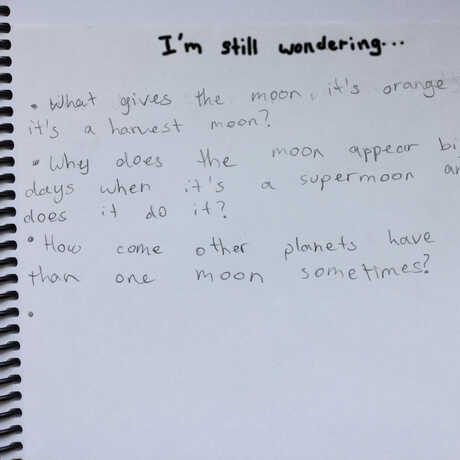

Erica taught a 5th grade unit on the phases of the moon. After keeping moon journals and manipulating several models, students practiced explaining the phases of the moon to each other.

At the end, Erica asked her students – what are you still curious about? Here are a few examples of their questions: “Has the back of the moon ever been lit up?” “Why is the moon linked to the sea?” “If the sun disappeared, where would the planets go?”

Erica wondered, what should she do with all these lingering questions? Her students had pen pals from a city in France. She decided to establish a question exchange where students from both cities sent each other their lingering questions about the moon. Her students were excited to realize that kids on another continent were looking at and wondering about the same moon!

Science Notebook Corner

Learn how notebooks can help your students think and act like scientists.