If someone were to ask you if you had heard of a bird called a Booby, you might instantly think of the Blue-footed Booby (Sula nebouxii). They breed on the Galapagos Islands and are named for their feet that are an unnatural-seeming shade of blue. Blue-footed Boobies have one of the most charming mating dances I’ve ever seen – they’re no birds-of-paradise in the dancing department, but still flashy in their own way (go look up some videos online – you won’t be disappointed.)

Large seabirds that are often found in tropical waters, Boobies are a spectacular group of birds. Like pelicans, they dive into the water from a great height to pursue fish, and have air sacs under their facial skin to help cushion the impact when they hit the water. There are six species in the genus Sula: the Masked Booby (Sula dactylatra), Nazca Booby (Sula granti), Brown Booby (Sula leucogaster), Blue-footed Booby (Sula nebouxii), Red-footed Booby (Sula sula), and Peruvian Booby (Sula variegata). We don’t usually get a chance to see them up here in Northern California, but occasionally one will be sighted somewhere along the California coast.

Recently, the marine mammal Curatorial Assistant from our department, Sue Pemberton, was called out to Bodega Bay to respond to a California Sea Lion stranding. This is a typical call for Sue to get, as she takes measurements and samples from dead marine mammals that wash up on the beach. Sue noticed that there was something else washed up nearby: a seabird (pretty typical, again, to find on the beach). When she got close, she realized that it looked like a Booby, which was a shock to her as they’re not common in California. After bringing it back to CAS, it was identified as a Brown Booby. Not only was this a rare species for us it get, it turned out to be the first Booby record ever in Sonoma County – no species of Booby had ever been seen there. What a find!

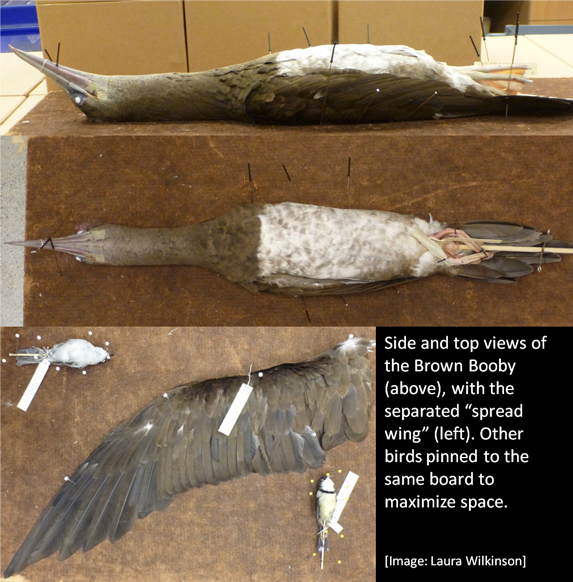

I didn’t think it would be salvageable as a study skin, as it had been partially scavenged by other animals. I was determined, however, to give it a shot. Such a rare specimen deserved to be preserved in a way that researchers could look at its feathers, as opposed to just its bones. I quickly found out that it was skinnable and that the holes scavenged by other animals could easily be sewn up. I also decided to detach one wing and prepare a “spread-wing” so that researchers could see all of the flight feathers. After getting a good bath to remove all of the sand, it ended up looking great.

This is one of the things that I love about my job: getting to do the hands-on work to prepare unique specimens for the research collection. Even though I’ve seen Brown Boobies when traveling in Central America and Mexico, it’s still exciting to see one up close and I never thought that I would get the chance to prepare one. This specimen will be an important addition to our collection for many years to come!

Laura Wilkinson

Curatorial Assistant

Ornithology & Mammalogy