Please note: Osher Rainforest will be closed for maintenance Jan. 14–16.

Science News

CSI: Iceman

May 3, 2012

We now have the world’s oldest human blood cells—thanks, once again to Ötzi the Iceman, whose untimely death in the Alps just keeps giving and giving, even 5,300 years after the fact.

Researchers decoded his DNA. Samples from his stomach and intestines have allowed us to reconstruct his very last meal. The circumstances of his violent death appear to have been explained. But his blood remained a mystery: scientists searching his veins and arteries never found even a trace of blood.

“Up to now there had been uncertainty about how long blood could survive—let alone what human blood cells from the Chalcolithic period, the Copper Stone Age, might look like,” says Albert Zink, head of the Institute for Mummies and the Iceman.

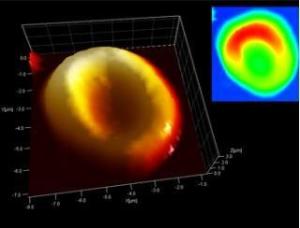

Enter Zink and his colleagues. This time, the researchers decided to look at Ötzi’s wounds—where the arrow entered his back and a laceration on his right hand. The team used an atomic force microscope to investigate thin tissue sections from the two spots. This nanotechnology instrument scans the surface of the tissue sections using a very fine probe. As the probe moves over the surface, sensors measure every tiny deflection of the probe, line by line and point by point, building up a three-dimensional image of the surface.

What emerged was an image (above) of red blood cells with the classic “doughnut shape,” exactly as we find them in healthy people today.

In addition, the team discovered that Ötzi likely died quickly. At the arrow wound, they identified fibrin, a protein involved in the clotting of blood. “Because fibrin is present in fresh wounds and then degrades, the theory that Ötzi died some days after he had been injured by the arrow, as had once been mooted, can no longer be upheld,” explains Zink.

The findings are published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

Image courtesy of European Academy of Bozen/Bolzano