We're open daily! View holiday hours

Science News

Hot Jupiters

September 4, 2013

By Elise Ricard

Recently, the search for extrasolar planets (a.k.a. exoplanets) has centered around finding an Earth-like world, a place where life as we know it could exist. After all, wouldn’t it be exciting to discover extraterrestrials—or at least a new place humans could inhabit? Problematically, these small, potentially inhabitable planets are terribly challenging to detect. Twenty years of searching has yielded 941 (and counting) confirmed planets, but none very much like Earth… Although we are well on our way to finding such a “Goldilocks” world (not too hot, not too cold, but juuuust right), other, often larger exoplanets are proving easier to find and uniquely interesting.

A significant percentage of the exoplanets uncovered so far are “hot Jupiters”—colossal gas giant worlds that equal or surpass the mass of Jupiter and orbit very close to their parent stars, creating high surface temperatures as a result. One particularly interesting giant is HD 189733b, a massive world a mere 63 light years away. Though discovered in 2005, its proximity to our solar system makes it a good exoplanet to examine.

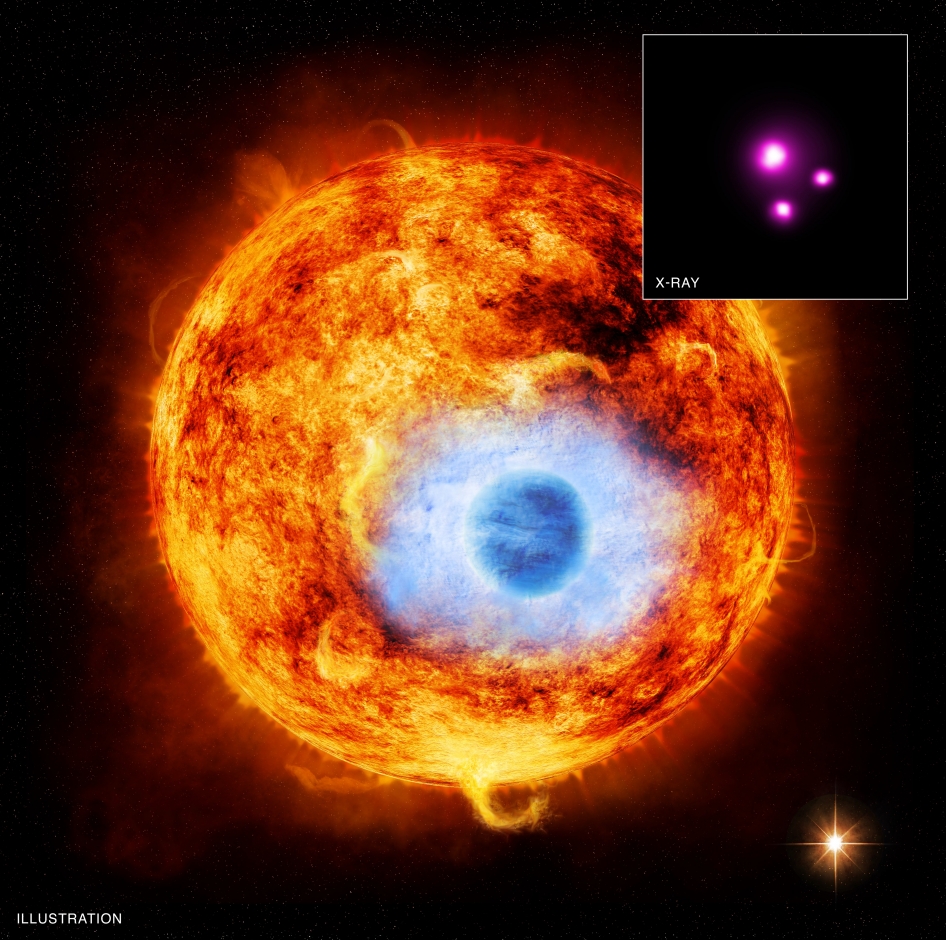

Some of the more interesting recent studies of this exoplanet leave behind the question of habitability to examine different planetary characteristics. In 2008, astrophysicists used polarimetry to detect and monitor the planet in visible light and determined an overall color of the world as it would appear to us. A second set of independent tests came back just this last month with the same result. The planet, as we would perceive it, is cobalt blue!

The discovery of another blue marble in the Milky Way is enticing. But this blue color is obviously not due to liquid oceans covering its surface. So where is the color coming from? It could be caused by a slow shower of molten glass. Observations have shown the likely presence of silicate particles in the lower atmosphere. This would scatter light in such a ways as to appear blue in the visible spectrum. Silicate is a component of glass which has lead some researchers to suspect the atmosphere might rain intensely heated bits of molten glass. Certainly not a storm you would want to be caught in!

Looking closer at the planet, all similarities to Earth continue to sizzle away. Orbiting 30 times closer to its star than Earth is to the Sun (which works out to about 13 times closer to its star than Mercury is from the Sun), this planet definitely qualifies as a HOT Jupiter: 1,200°F (650°C) on the night side to 1,700°F (930°C) on the day side with winds as fast as 6,000 miles per hour (nearly a thousand kilometers per hour). This is not a life-friendly place. In fact, Scott Wolk of the Center for Astrophysics estimates the atmosphere of the planet is boiling away at about 660,000 to 100 million tons of mass per second.

HD 189733b is a fantastic example of the surprises that continue to amaze us as we learn more about our universe. Hot Jupiters are not places we study in the hopes of finding life. Rather, we explore these fascinating places so different from our own world to learn about the diversity of planetary systems in our galaxy. They help us uncover more about the evolution of planets and allow us to probe the conditions that came together to form the immense diversity of worlds that we see. They provide clues and contrasts to our own planet, where the processes of life were able to take hold and evolve.

Could Earth have once been a hot Jupiter instead? Quite unlikely. Can HD 189733b ever be the next Earth? Not likely. But these bizarre and far-off worlds are certainly engaging in their own right.

Elise Ricard holds a master’s degree in museum education and is a presenter at Morrison Planetarium.

Images: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO/K. Poppenhaeger et al; Illustration: NASA/CXC/M. Weiss