Science News

News from our Solar System and Beyond

Flowing Water on Mars

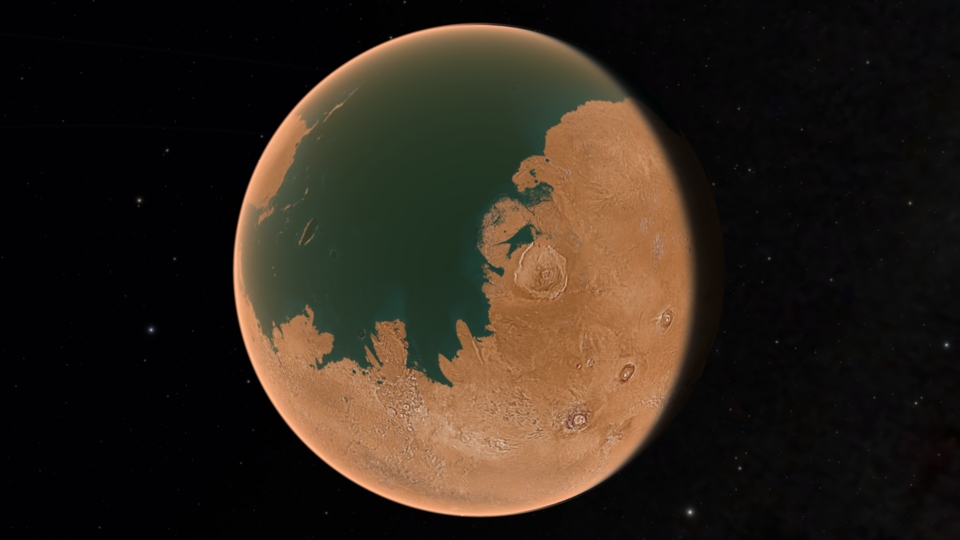

Mars is an incredibly dry planet now, but we have ample evidence that water once existed on the Red Planet. A paper in Nature Communications this week reports that water may have been even more abundant during certain periods in the planet’s past than previously thought.

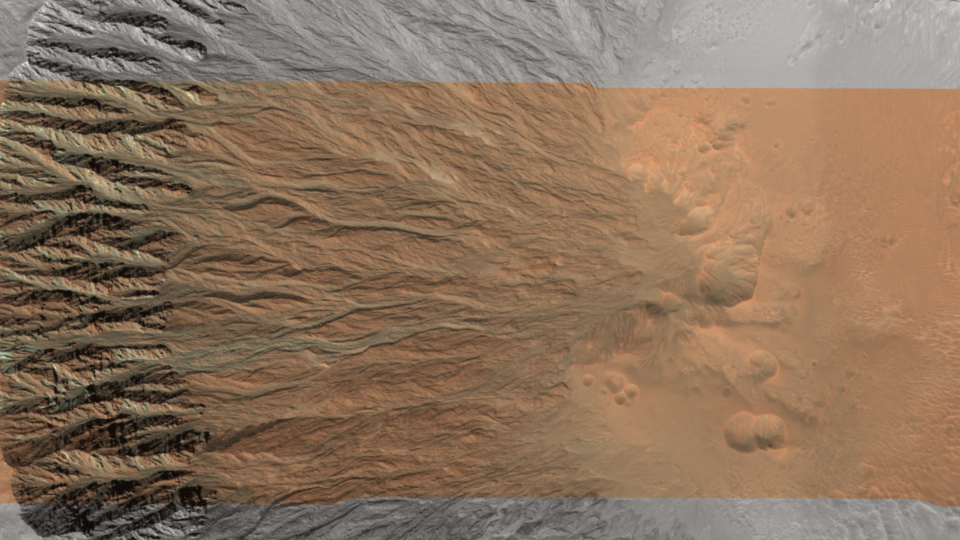

Scientists studied evidence of ancient water on Mars in the form of debris flows in the Istok Crater towards the equator. Debris flows are similar to mudslides on Earth—a bit of water and a lot of debris sliding down a slope or mountain. The team then created physical models in the lab of these flows to see exactly how much water would have to be present to create the patterns seen in the crater.

They found that there were many more frequent debris flows than previously thought, likely due to periods of “high obliquity” (or large axial tilt) when the weather would have been warmer causing ice to melt and snow to fall. Mars’s axis is known to tilt much more dramatically than Earth’s. The Christian Science Monitor reports that “its axis is currently tilted 25 degrees, but during high obliquity intervals, Mars is lying down almost sideways with respect to its orbit, like Uranus does,” obviously wreaking havoc on the temperatures and ice on the cold planet.

Given this variability, the scientists say these large water flows could occur again, and quite soon on a geological time scale—within the next few hundred thousand years or so! –Molly Michelson

Rosetta is Go for Landing—WHAT?

On Tuesday, June 23, European Space Agency officials approved a nine-month mission extension for the Rosetta spacecraft, which recently re-established contact with the Philae lander on Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Observing the dynamic changes taking place on the comet’s surface, Rosetta will accompany 67P as it rounds the Sun in August. Then, a year later, after the comet has pulled far enough away from the Sun for the heat-induced activity to subside, the environment surrounding the comet should be safer to attempt something Rosetta wasn’t designed for—a risky touchdown on the comet’s surface. Risky indeed, considering that plunking down on the comet was tough enough for the spindly little Philae probe, which bounced off the surface in spite of the fact that it was designed to land on the comet.

Only one other spacecraft ended its mission with a landing attempt it wasn’t originally intended for. NASA’s NEAR (Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous)-Shoemaker vehicle orbited the asteroid Eros for a year, then was carefully, and successfully, steered lower for a gentle touchdown on the asteroid’s surface in 2001. It continued collecting in-situ data on the asteroid’s surface for six days.

Similarly, if all goes well roughly 15 months from now, the finale of Rosetta’s mission will involve slowly lowering the spacecraft’s orbit, guiding it to a smooth, flat area in a maneuver more akin to a slow docking than actually landing. That way, even in the comet’s extremely weak gravity, Rosetta won’t bounce back off into space, as Philae nearly did. –Bing Quock

Pluto Awaits!

In less than three weeks, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft, launched in 2006, arrives at the Pluto system, zipping past the planet and its five (maybe more) moons. One of the fastest spacecraft ever, departing Earth roughly 100 times faster than a jetliner, New Horizons crossed the orbit of the Moon in less than nine hours—a journey that took the Apollo missions four days. It reached Jupiter in a mere 13 months, where it received a 9,000 mph (about 15,000 kph) boost in speed. But the mission has taken nine years to get to Pluto, which it will encounter on July 14.

When New Horizons was launched, Pluto was still called a planet, so mission planners boldly proclaimed the project to be “the first mission to the last planet.” Then, the International Astronomical Union decided that Pluto isn’t a planet anymore, reclassifying it as a “dwarf planet.” On top of that, for a while it wasn’t even thought to be the largest of the dwarf planets—a point still being argued, as its fellow-dwarf planet Eris is approximately the same size. Finally, New Horizons isn’t even the first mission to a dwarf planet, let alone to “the last planet.” Since March, NASA’s Dawn spacecraft has been orbiting the reclassified dwarf planet Ceres, making Pluto the second dwarf planet to be visited this year.

But the debate does not stop there. Spacecraft have visited planets and comets, but never have we visited an object that could arguably be said to be both. Pluto crosses inside the orbit of Neptune once each trip around the Sun, spending 20 years closer to our star than that its big blue brother. During that time, it develops a detectable atmosphere, the same way a comet develops a coma as it approaches the Sun. But while in some ways resembles a comet, no comets that we know of have five moons, like Pluto does. And Pluto represents not the last planet but the first Kuiper Belt object to be encountered, opening a new frontier into which the mission will continue.

The region beyond Neptune is littered with countless bodies, which include three other dwarf planets and the short-period comets (those that return to the Sun every 200 years or less), and New Horizons will be the first to encounter objects in this largely-uncharted realm. NASA has yet to decide which other Kuiper Belt object the spacecraft will visit, pending the outcome of the Pluto encounter. So even if New Horizons isn’t the first mission to the last planet, it will undoubtedly be the first to explore an exciting new region of the Solar System. –Bing Quock

Exoplanet “Bleeding” Its Atmosphere

Findings reported this week in Nature from the Hubble Space Telescope reveal a phenomenon never before observed around an exoplanet—an immense cloud of hydrogen “bleeding” off a gaseous planet, somewhat resembling a comet tail.

Only 30 light years from Earth, the Neptune-sized GJ 436b is very close to its red dwarf star—only about three million miles (five million kilometers) compared to the Earth’s 93 million miles (150 million kilometers) from the Sun. The planet’s surrounding hydrogen cloud, nicknamed “the Behemoth,” is 50 times its size. The Behemoth formed as X-rays from the close star evaporated the planet’s atmosphere away. According to Dr. Peter Wheatley of University of Warwick, about 1,000 metric tons of hydrogen burn off the atmosphere every second, or about 0.1% its total mass every billion years.

“This cloud is very spectacular, though the evaporation rate does not threaten the planet right now,” explains David Ehrenreich of the University of Geneva. “But we know that in the past, the star, which is a faint red dwarf, was more active. This means that the planet evaporated faster during its first billion years of existence. Overall, we estimate that it may have lost up to 10 percent of its atmosphere.”

Although the planet is not in danger of its atmosphere completely evaporating away, leaving only a rocky core, this process could explain the existence of “Hot Super-Earths,” rocky planets larger than Earth that reside very close to their stars. The team also speculated that this kind of evaporation may also have occurred to Mercury in our own solar system. Either way, the find is considered “game changing” by the team in analyzing and characterizing other exoplanetary atmospheres.

The cloud itself has likely not dissipated because the nearby star is relatively cool, so the cloud did not rapidly heat and become swept away by radiation pressure. It also reflects ultraviolet light from its star, meaning that Hubble’s UV instruments (and its location above Earth’s UV-blocking atmosphere) were necessary to detect the cloud. –Elise Ricard

Mars Image(s): Dan Tell