The Academy is working to regenerate the natural world. See where we're making a difference.

Sustaining Life

Investigating Strandings, Protecting Whales

Marine mammals are important harbingers for the health of Earth’s oceans. This is especially true of whales, who often rely on primary food sources like plankton and krill and have vast migratory patterns: Some humpback whales, for instance, swim 3,000 miles between Alaska and Hawaii every year. As global warming, pollution, and increased human activity continue to harm ocean habitats and unravel the marine food web, Academy researchers are working to make sure the warnings from these marine messengers are heeded.

As part of these efforts, the Academy’s Department of Ornithology and Mammalogy, along with our collaborators at The Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito, have been decades-long members of the Marine Mammal Stranding Network (MMSN)—a national research project led by the National Marine Fisheries Service.

Launched in the 1980s as a result of the Marine Mammal Protection Act, the network is a consortium of research institutions and nonprofits that respond to marine mammal strandings, rehabilitating or rescuing live animals and performing necropsies on deceased ones to collect invaluable scientific data. These data are then used to assess the threats these vulnerable populations face—and how best to protect them.

A whale of a problem

Between 1999 and 2000, more than 600 gray whales washed up on the West Coast during their annual migration between Baja California and Alaska, prompting the US government to declare the die-off an unusual mortality event (UME) and launch a formal investigation into the cause. Due to the suddenness and unprecedented scale of the event, however, only two of the whales received necropsies. The rest were disposed of or left for the ocean to reclaim, resulting in the loss of crucial data that could have been used to better understand their untimely deaths.

While UMEs are devastating in their own right, it’s what we don’t see that reveals the true extent of the crisis: It’s estimated that stranded whales only represent between 4 to 13 percent of whale deaths in a given year. The remaining majority either sink to the bottom of the ocean or are preyed upon by other species.

So, when another UME occurred in the summer of 2019, and more than 200 gray whales washed ashore along their migration route, the Academy and its collaborators all along the West Coast were ready. This time, nearly all of the 14 carcasses that beached in the Bay Area were necropsied, providing key data and insights into the increased morbidity.

“Each necropsy tells a story,” says Moe Flannery, the Academy’s Ornithology and Mammalogy collection manager and one of three California state coordinators leading the investigation into the recent UME. “Without the data we gather, researchers wouldn’t have the tools they need to understand why these animals are dying.”

After investigating nearly 700 whale carcasses between 2019 and the end of 2023, scientists found that the leading causes of death were malnutrition and vessel strikes. Previously collected data from the Academy and the MMSN has helped influence legislation seeking to protect vulnerable marine mammal populations, so the hope is that these more recent findings might do the same.

Making room for marine mammals

Whales are no longer the only seafaring behemoths, with cruise liners and cargo ships now carrying passengers and goods across the globe. In major ports, such as the Port of San Francisco, hundreds of large ships come and go each year, often traveling along the same routes used by marine mammals, leading to increased vessel strikes and mortality.

In the Bay Area, the problem has only gotten worse over the past few decades. As waterways and shipping lanes become more congested, more marine mammals end up in harm’s way. The increase in vessel strikes may also be a consequence of stronger local environmental regulations and overfishing offshore: As the water in San Francisco Bay becomes cleaner and offshore food sources are depleted, large marine mammals such as porpoises and whales are more likely to enter the healthier Bay to feed—and experience fatal run-ins with vessels.

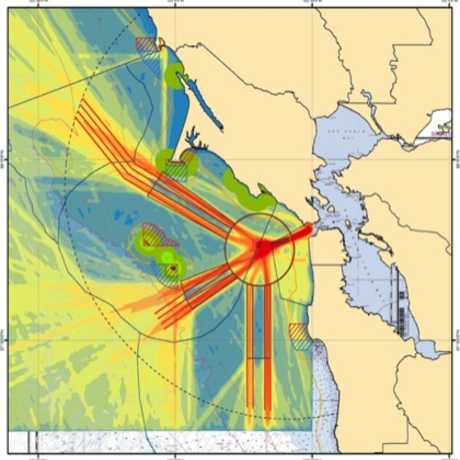

Recently, data from the Academy and the MMSN has helped bring about a change that could stem the tide of boat-related marine mammal deaths. In 2013, the shipping lanes surrounding the Farallon Islands just off the coast of San Francisco were adjusted and ship captains were encouraged to reduce their speeds while entering and exiting the Bay. In fact, many of the major shipping companies that use the port now attend an annual award ceremony honoring captains with the lowest average speeds throughout the year.

Since determining causal links to marine mammal strandings requires long-term monitoring of data, it’s too early to tell whether or not this change has reduced the number of vessel strikes around the Bay Area. Even though the most recent unusual mortality event has concluded, Moe and her team will continue responding to strandings and performing necropsies to ensure that stranded whales, in death, can provide the data needed to save more lives. “We’ll stay ready,” she says. “We’re committed to investigating what’s happening in our own backyard and protecting these iconic species.”

All marine mammals are federally protected by the Marine Mammal Protection Act. All marine mammal stranding activities depicted above are conducted under authorization by the National Marine Fisheries Service through a stranding agreement issued to the California Academy of Sciences and an MMPA/ESA Permit.