Scientist Spotlight

Brian Fisher

Brian Fisher is passionate about ants. He specializes in the large-scale discovery, description, and naming of African and Malagasy ants. His inventory work in Africa and Madagascar demonstrates the feasibility and challenges of conducting global biodiversity inventories.

Read more about how Fisher is scaling edible insect farming to support both people and forests on the island nation—and eventually beyond—in a new feature from TIME Magazine.

Learning ants

Brian Fisher, the California Academy of Science's renowned entomologist, reveals there are 22,000 species of ants populating the earth. “Our ability to dig deeper into their hidden world can shed light on important ecosystem functions that have been overlooked out of ignorance or disinterest,” says Fisher.

“Consider that the collective weight of all the ants in the world is equal to the weight of all the world's humans. It's a big subject with a big impact. That alone makes ants worthy of scientific study.”

Fisher has committed his life to exploring the world of ants. The fact that ants are industrious, tenacious workers who live in colonies and obey a hierarchy of rulers is well known. In fact, it mirrors qualities found in humankind. But Fisher's studies go well beyond these characteristics. For the last 23 years, he has traveled the globe finding, collecting, identifying and naming ants, describing their behaviors, and cataloguing their traits. There are an estimated 22,000 ant species known to science. Fisher has personally discovered 1000 species of these.

His love affair with ants was spontaneous. Born in Normal, Ill., the son of a college professor and a fifth grade teacher, Brian Fisher knew he wanted to work in the outdoors but not as a park forester in a park. Flying to Europe the day after his high school graduation, he spent two years bicycling the continent, learning French and carpentry before returning home.

Once back, he enrolled at the University of Iowa, majoring in biology. “But I was itching to get to Latin America, learn Spanish and live the dream of a tropical plant collector,” he remembers. It was during a year in Panama that he worked part-time for the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. He also worked as an aspiring botanist, collecting specimens of tropical flora. It was during his stay in Panama that the love bug bit.

“You go to the tropics and the sheer diversity of insects are literally raining down on you,” says Dr. Fisher. “At that point, I decided to switch from being a great botanical explorer to becoming an ant finder.”

Madagascar

The first ant was discovered in 1758 by the European biologist Carl Linnaeus. It was Linnaeus who invented the naming system for ants that is part of the National Code of Zoological Nomenclature.

The first ant? Actually, there were two. “Fomica fusca and Formica rufa, or black ant and red ant,” says Fisher.

While Fisher's base camp is the Academy's San Francisco-based facility, the lion's share of his work for the last six years has been in Madagascar, the fourth largest island in the world off the coast of Africa. This island boasts 5 percent of the world's total plant and animal life.

“It is a living laboratory for understanding the world's ecosystems,” Fisher explains. In his field research to Madagascar, the entomologist has done much more than just inventory ants. His work has helped the island nation, which is 90 percent deforested, preserve what is left of its environmental health.

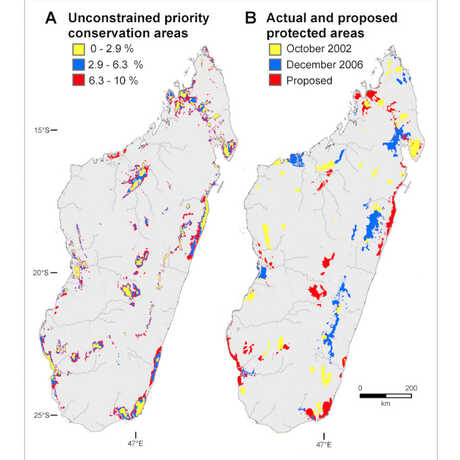

In just one six-week expedition, he piled researchers into a Toyota Land Cruiser (often doing double-duty as a submarine for river crossings) braving floods, drought, and a national revolution in order to dig up data on insect and spider diversity. The research team also helped the island set its conservation priorities.

“Our work on Madagascar is one of the largest insect inventory project ever undertaken,” says Fisher. “We have set traps and collected one million specimens at 200 sites across the island.” Over the years, Fisher has identified and named 900 ant species on Madagascar alone. That's a large percentage of the total number of species—1,000—that he's discovered so far in his professional career.

Tree of life

Brian Fisher is currently pursuing two specific goals. For the past three years, he has been constructing a “tree of life” for ants. This project aims to map the genealogical and evolutionary history of ants, which, he adds, evolved from wasps. In the past, this work would have moved at a snail's pace. Now, using molecular data—the equivalent of ant DNA—the process by which scientists can understand the “trunk, branches and twigs of the genetic tree” has greatly accelerated.

Can Fisher and other scientists finally get to know all 22,000 inhabitants of the ant world? Not quite. “I can't describe all the species of ants in the world,” he explains. “But I expect to describe all the ants living in Madagascar.”

As a scientist, Fisher's vision seeks to benefit future society, not just ant lovers. He often circles back to his true dream of eliminating bio–illiteracy. “As people move to cities worldwide, we become less and less connected to the environment,” he explains. “To really understand it and track changes, we should have a Dow Jones Index for the environment—a spectrum of all the elements and processes in the ecosystems.”

As he sees it, the most current scientific data on plants, ants, animals, water, air, marine life, and temperature change would be represented in the index. “This tool would enable us to give a voice to the insects, especially ants. That's crucial because they give us back the most data on the environment than any group. Their life cycle is shorter, they change very quickly,” he says. “Everyone has run into ants. Now we need to listen to them.”

Amazing ants

On his many expeditions, Fisher has uncovered literally a thousand new species of ants. Among his more extraordinary finds include the trap-jaw ant. He collected this species while on a trip to Costa Rica with other entomologists to focus on ants that build nests out of their own body. Instead, the trap-jaw ant became the focus of his work. Fisher learned that this native Costa Rican species can snap its jaws shut at up to 145 miles-per-hour to capture prey, chase off enemies or dash for safety. “It's the fastest self-powered strike on record, faster than a cheetah,” he says. The trap-jaw ant can also go airborne to catapult itself out of harm's way.

Fisher also identified and named the “Dracula ant” during his work in Madagascar. This ant species consists of adults that suck the blood out of the larvae of their offspring to feed themselves. Adult ants cannot eat solid food. In more sophisticated species of ants, the babies function as the “social stomach” for the colony as they eat, regurgitate their food, and pass it along to other ants.

Finding new species has become somewhat easier for Fisher and other entomologists. He credits this ease with the invention of Google Earth. “Before Google Earth,” he explains, “you needed names of species to track down their locale. Now you just pinpoint a spot in the world for armchair exploration.”

To show his appreciation for this new tool of technology, when Fisher discovered another new ant species in Madagascar he named it the “Google Ant.” “The Google Ant hunts for very obscure prey—spider eggs exclusively. Google Earth allows you to zero in from a satellite in space to, say, your own backyard, to see what ants, insects and other living organisms live there. I saw a connection!”

Department: Entomology

Title: Curator of Entomology, Patterson Scholar

Expeditions: 50

Current Expedition: Madagascar

Articles:

"Farming Insects to Save Lemurs" [bioGraphic]

Videos:

Tracking Ants Around the World

Into the Wilderness

Miracles of Ants

Related Websites:

Brian's IBSS staff page

Q&A with Brian Fisher

AntWeb

Opportunities:

Ant Course

Academy entomologists study flies, beetles, ants, butterflies, moths, spiders, scorpions, and more. Meet the curators and researchers, explore projects and expeditions, and search their collections.