Scientific Expeditions

Galápagos Islands Research

The California Academy of Sciences has a deeply rooted history of research in the Galápagos—islands long heralded by scientists as living laboratories of evolution. Since sending our first expedition to these storied islands in 1905, the Academy has organized dozens of return trips while helping to found both the Charles Darwin Research Station (at Academy Bay) as well as Galápagos National Park.

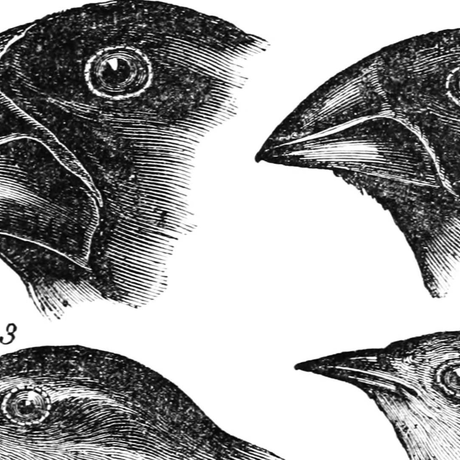

The Academy is home to the world's largest collection of scientific specimens from the Galápagos, most notably a finch collection so significant that it continues to help modern-day researchers answer scientific questions. The majority of our Galápagos field work now focuses on the marine environment, where dozens of new species have been discovered in the last decade. Learn more about a handful of our Galápagos expeditions below.

1905-1906: The First Expedition

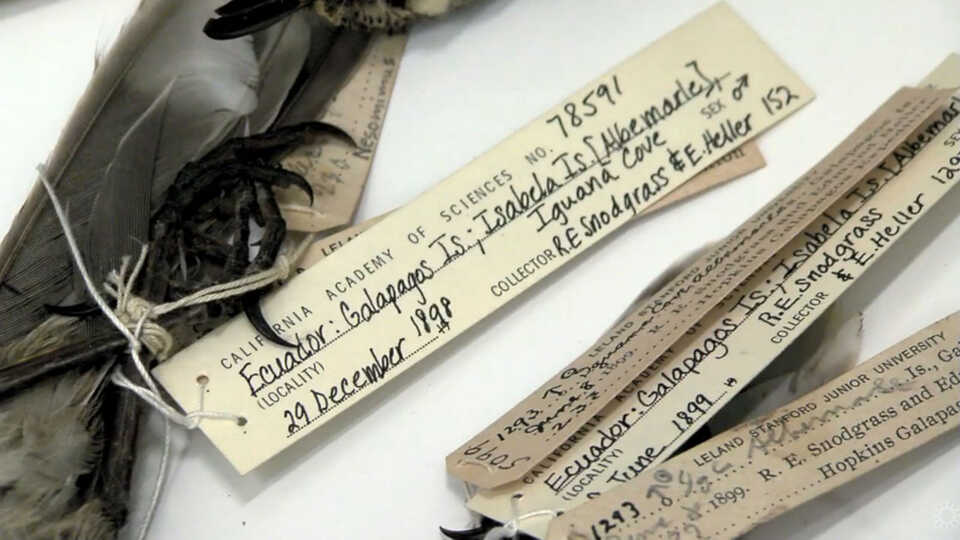

The Academy sent its first team of “sailor-scientists” to the Galápagos in 1905. Among them were collectors Alban Stewart, Rollo Beck, Edward W Gifford, FX Williams, Joseph Hunter, Joseph Slevin, and Washington Henry Oschner (whose field notes from have been archived in the Biodiversity Heritage Library). During this time, there was a widely held belief that species on the Galápagos, especially the iconic giant tortoise, were quickly disappearing. Thus, the men sought not only to explore the islands but to gather as many plants, mollusks, insects, birds, mammals, and reptiles as possible for museum collections. They also hoped to use these specimens to shed light on the origins of the islands.

The crew of the "Academy" research vessel returned to San Francisco in 1906 with 70,000 biological specimens, the most gathered on any Galápagos expedition in history. But while they were away, the April 18, 1906 earthquake and fire destroyed the Academy’s building (and much of its collections) on Market Street, making the specimens the men gathered critical to rebuilding the museum. Today, despite being more than a century old, the Academy’s Galápagos collection is still actively used by scientists for a wide variety of studies.

1932: Aboard the Zaca

In 1932, explorer and heir Templeton Crocker funded an expedition to the Galápagos and nearby areas on his schooner, the Zaca. On this trip, Academy scientists undertook an unprecedented effort to share the living laboratory of the Galápagos Islands with the public, collecting more than 300 live specimens—including termites, ants, and mollusks—for display at the Steinhart Aquarium in Golden Gate Park.

1960: Galápagos International Scientific Project

The 1960 opening of the Charles Darwin Research Station on Academy Bay (named after the California Academy of Sciences) marked the beginning of an international initiative to conduct modern research in the Galápagos. With support from the National Science Foundation, University of California Berkeley Extension, and the Charles Darwin Foundation, the Academy helped launched the Galápagos International Scientific Project.

The project sought to extend the studies Darwin had made of the geology, climate, ecology, and of the plant and animal species of the islands, which were under threat from the increasing population moving in from the South American mainland. For 11 weeks, more than 60 scientists (including 10 Academy biologists) explored remote areas by helicopter, tagged and monitored the island’s giant tortoises, generated the first complete list of Galápagos flora, and discovered dozens of new species.

1990s-Present: Searching the Seas

In recent decades, the Academy scientist John McCosker, Chair of Aquatic Biology, has led our Galápagos research efforts. McCosker has spent nearly 30 years studying the composition, relationships, and origins of Galápagos fishes, and in 1994, McCosker organized a Galápagos marine biotic survey with colleagues from the Academy, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and the National Fisheries Institute of Ecuador. Almost two dozen species new to science were found, including 18 new species of nudibranchs described by Academy Invertebrates Curator Terry Gosliner. McCosker also added 11 new species to his list of Galápagos shore fishes.

McCosker and colleagues have used the Johnson Sea-Link, a helicopter-sized deep sea submersible, on multiple expeditions to survey Galápagos marine life 3,000 feet below the water's surface. Their research has revealed new species of fish and invertebrates, new animal behaviors, and startling observations of the effects of El Nino on local marine biota.

McCosker’s most recently discovered Galápagos species is a type of deep-sea cat shark, the description for which he published in 2012. (The shark, which was described from seven specimens, is approximately a foot long with a chocolate-brown coloration and pale, irregularly distributed spots on its body.) Though McCosker has ventured to the Galápagos many times, his expedition goals have remained the same: to contribute to our knowledge of nearshore fish evolution and island biogeography, and to advise the Ecuadorian government on its resource management policies.

The Department of Ichthyology is home to one of the largest and most important collections of fishes in the world, and is designated as one of eight International Centers for Ichthyology in North America. Meet the researchers, explore projects and expeditions, and more.