The Unsung Heroines of the California Academy of Sciences

In August 1853, a group of men at the California Academy of Sciences gathered to pass a motion allowing for women’s involvement in Academy work: “We highly approve of the aid of females in every department of natural science, and [...] we earnestly invite their cooperation,” the resolution read.

This motion, passed four months after the founding of the Academy, was a curiously progressive allowance at a time when men overwhelmingly dominated scientific fields and few research organizations allowed for, let alone paid, female staff. Yet women’s integration into the Academy was by no means an easy or quick process: An early Academy publication noted that it took “a number of years” for women to accept “the invitation thus so gallantly held out to them.”

Indeed, it took 25 years for women to become resident members of the Academy—affiliated scientists nominated and elected by leadership. The Academy appointed its first female curator in 1883, but the distribution of male and female curators in the Academy’s 171-year history overwhelmingly skews male.

In honor of Women’s History Month, learn the “Untold Stories” of pioneering women in the Academy’s history. These stories were compiled by Academy Library staff and Careers in Science high school interns, who dug through archival materials to better understand the people who built the Academy into the scientific organization it is today.

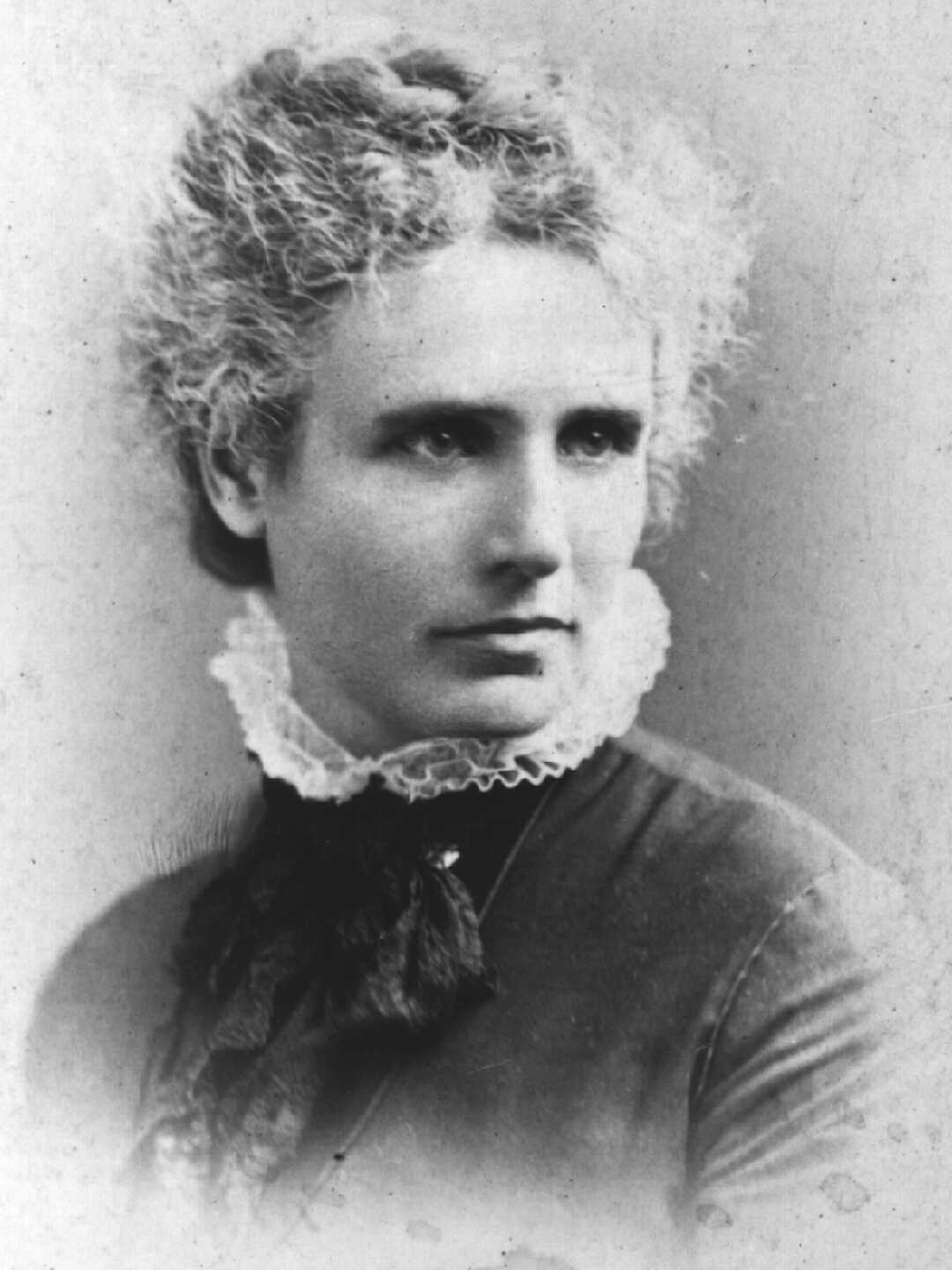

M. Katharine Brandegee (1844-1920)

Initially trained as a medical doctor, Katharine Brandegee, MD, was unable to establish a practice due to sexism from potential patients. This led Brandegee to the California Academy of Sciences, where she developed her passion for botany and eventually rose to the rank of curator—the first woman at the time to hold that position in a scientific museum and at the Academy.

Alice Eastwood (1859-1953)

One of the Academy’s first female curators of botany, Alice Eastwood is well known for her storied career describing hundreds of plant species. She was a self-taught botanist who dramatically expanded the Academy's collections.

Eastwood became a legend among Academy curators after she broke modern-day OSHA regulations in a daring bid to save dozens of Academy specimens from the 1906 earthquake.

See how Dr. Sarah Jacobs, Curator of Botany describes Eastwood’s legacy.

Harriet Exline Frizzell (1909-1968)

An avid arachnologist, Harriet Frizzell, PhD, discovered roughly 500 new species of spiders in her lifetime, publishing extensively on their behavior and the diet of black widow spiders. She married another scientist and worked for the Academy as an independent researcher who operated out of her Missouri home.

Frizzell was the first woman in the United States to obtain a doctorate in arachnology, but never held a fully paid position in arachnology for her entire life. Her scientific legacy is often overshadowed by her role as a housewife and homemaker.

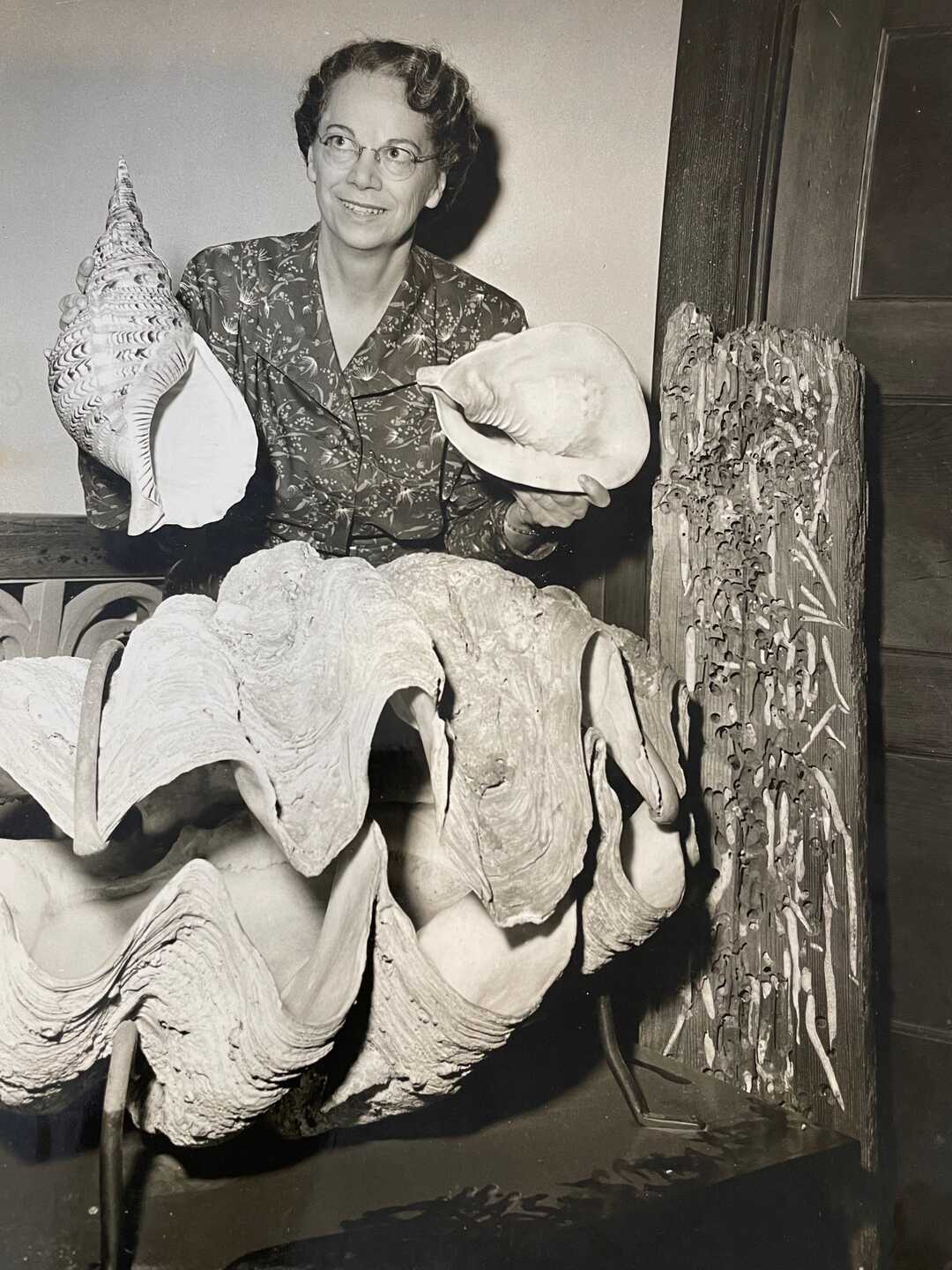

A. Myra Keen (1905-1986)

Mollusk and shell specialist Myra Keen, PhD, first developed her passion for invertebrate paleontology as a volunteer researcher at Hopkins Marine Station in Monterey, California. Keen ascended to the rank of full professor of geology at Stanford University in 1965, but was not fully compensated for much of her career as a direct result of the sexism women faced in academia.

Keen’s experiences spurred her to speak out against a variety of topics including fair pay, unfair beauty standards, the protection of marine ecosystems, and the U.S. government’s historic and ongoing harms against Indigenous people. Keen was so beloved as a professor and researcher that she curated an entire exhibit based on correspondences she had with fans and people who loved shells.

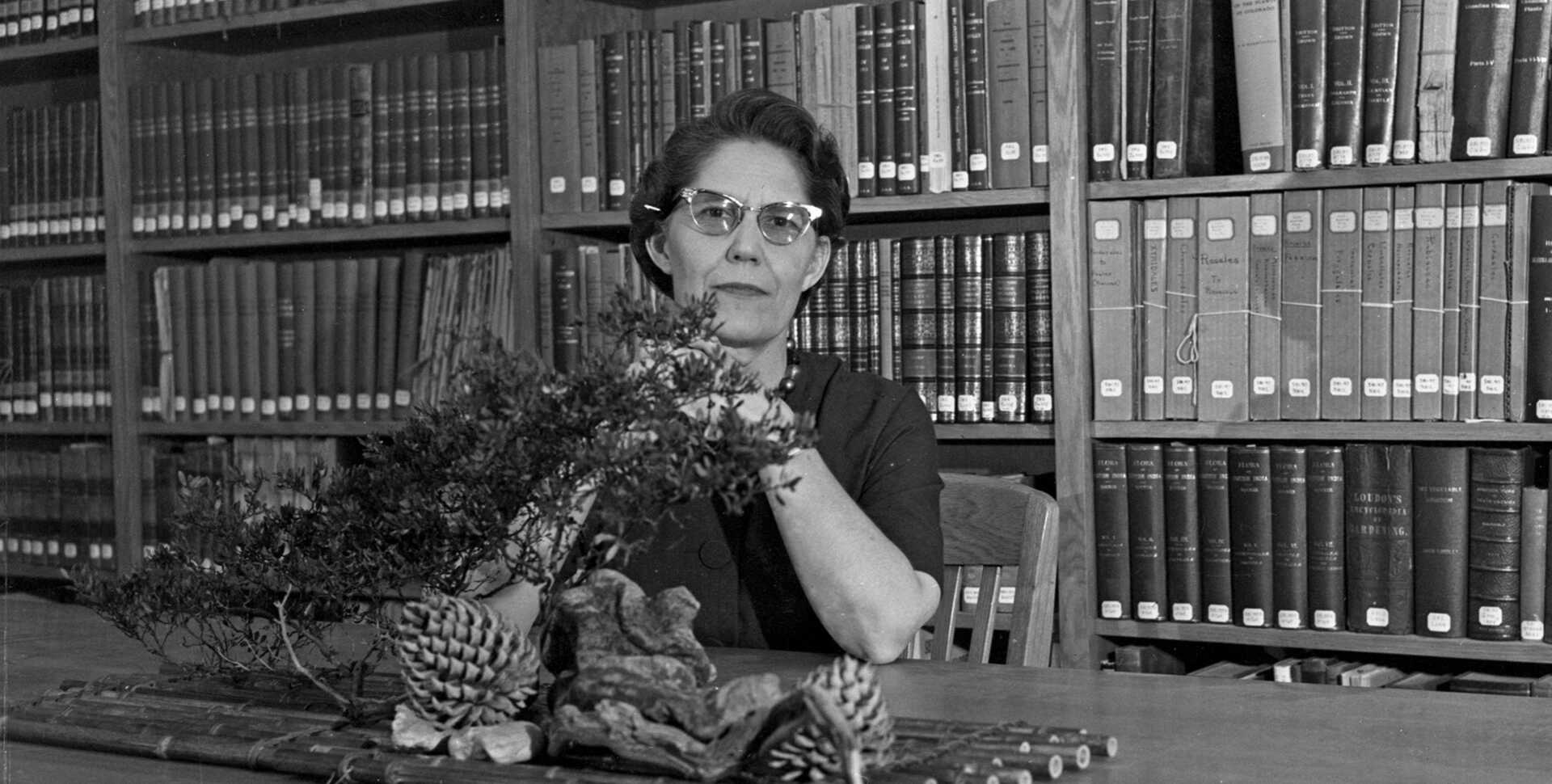

Elizabeth McClintock (1912-2004)

Elizabeth McClintock, PhD, served as the Academy’s curator of botany from 1949 to 1977, specializing in ornamental plants such as hydrangeas, manzanitas, and sunflowers. Though McClintock was the first botany curator at the Academy to hold a PhD, her contributions were woefully undervalued by Academy staff, who wrote off her research, treated her like a secretary, and severely underpaid her.

McClintock was nevertheless passionate about environmental activism, protesting against the development of the Golden Gate Panhandle freeway and other new construction that threatened California's fragile ecological balance.

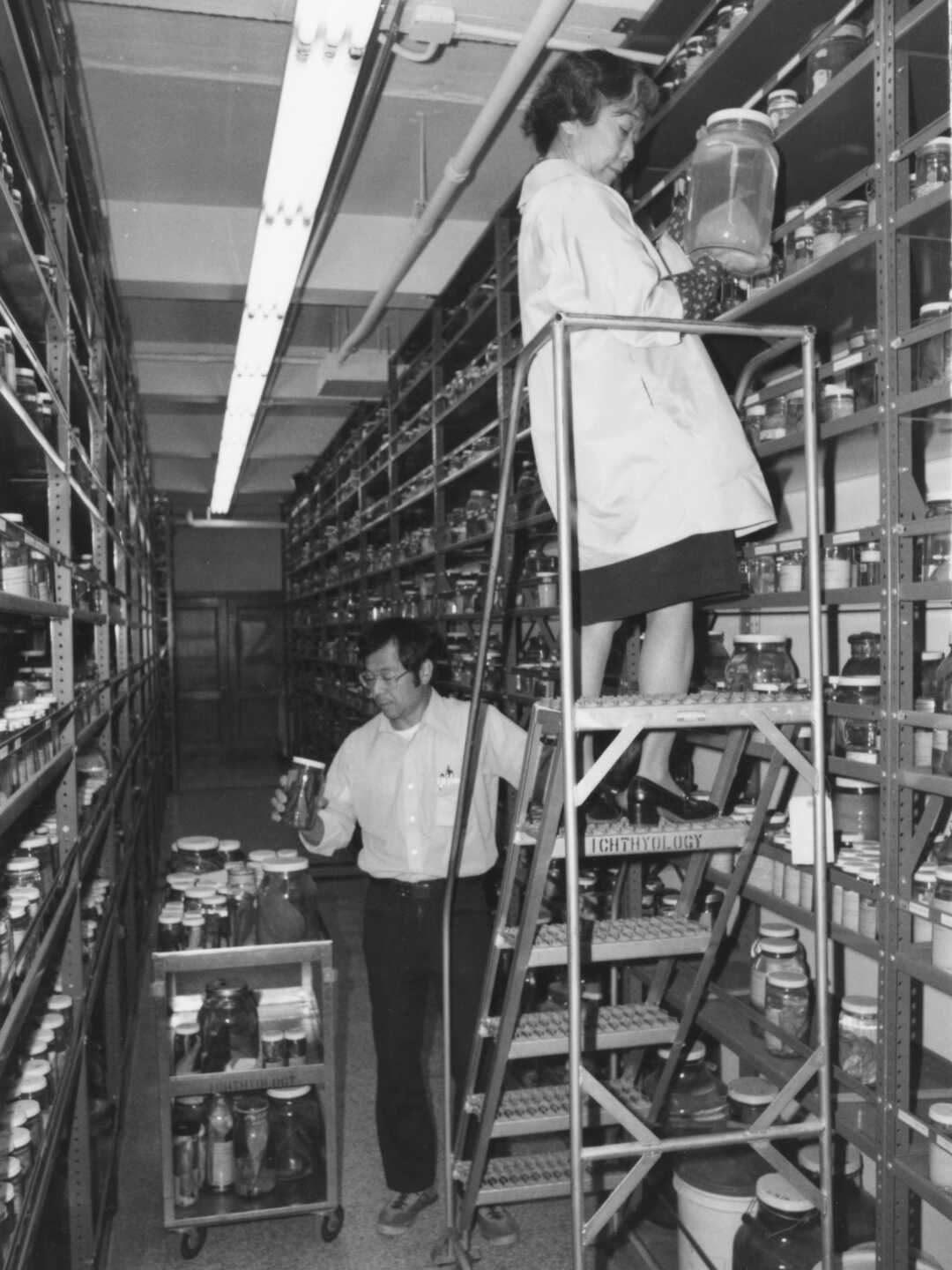

Pearl M. Sonoda (1918-2015)

Before embarking on a career working for various natural history museums, Pearl Sonoda was one of thousands of Japanese Americans forced into incarceration camps during World War II. Sonoda’s interests in biology eventually became the cause for her release in 1943, when she joined Chicago’s Field Museum. Sonoda later came to the Academy in 1967 and served as senior curatorial assistant in the ichthyology department, managing thousands of fish specimens.

When male researchers reached out to inquire about Academy collections, they often addressed letters with “Dear Sirs” or “Dear Gentlemen.” Sonoda always responded by emphasizing the “Miss” title in front of her name. Sonoda’s colleagues in the ichthyology department remember her as both the “sweetest lady” and a “real strong person” who pushed boundaries in her nearly thirty years of Academy service.

Today, the Academy looks like a very different place than when it was founded in 1853, with far more women among the ranks of curators, collections managers, and research staff. More work still needs to be done to truly strive for gender inclusion and equity in science, particularly for women from other marginalized backgrounds, including race, socioeconomic status, and sexuality.

Yet dozens of scientists of color and LGBTQIA+ researchers are driving crucial changes in the field, carrying forward the efforts of the early women in the Academy. Their work is spotlighted at exhibits such as New Science: The Academy Exhibit, and in Seeing It All, a new wildlife photography book featuring the work of 11 visionary female photographers and their work in rarely seen locations around the world.